How to Price Your Product: A Pricing Model Decision Tree

Recently, we published an edition called How to Price Your AI Product, co-written with DealOps, that went through critical considerations for pricing. The demand that we got for more pricing information was overwhelmingly positive.

We wrote this edition to answer that call and build out a true pricing model decision tree, along with a full guide for determining what pricing makes sense for you.

Why? Pricing is not a math problem.

Pricing is a go-to-market decision that shapes how fast you sell, who buys first, how accounts expand over time, and how durable your revenue becomes over the long haul. And yet, despite how much weight this decision carries, most founders still start with the wrong question: “What should we charge?”

That question puts the cart before the horse. It jumps straight to a number before you’ve figured out the structure. The better question, the one that actually sets you up to win, is: “How should customers pay us, and why?”

The “how” is your pricing model – seats, usage, outcomes, platform tiers, or some hybrid of the above. The “why” is the alignment between that model and how your customer actually experiences value. Get the model right, and the price point conversation becomes dramatically easier. Get it wrong, and you’ll spend months fighting friction that no discount or packaging trick can fix.

In this edition, you’ll learn how to use a pricing model decision tree, what we call the “Waterfall” to find the model that fits your product, buyer, and market before you ever debate price points. We’ll cover how your market type and product category shape every pricing decision, walk through a step-by-step if-this-then-that logic flow to land on the right model, look at how real companies chose theirs, and flag the common mistakes and exceptions that trip founders up.

HockeyStack is the AI platform for modern GTM teams. It unifies all your sales and marketing data into a single system of action. Built-in AI agents help teams prospect the right accounts, improve conversions, close and expand deals, and scale what works.

That’s why teams like RingCentral, Outreach, ActiveCampaign, and Fortune 100 companies rely on HockeyStack to eliminate wasted spend, take better decisions, and make space to think. Learn more at hockeystack.com

The Foundation: Market & Product Type

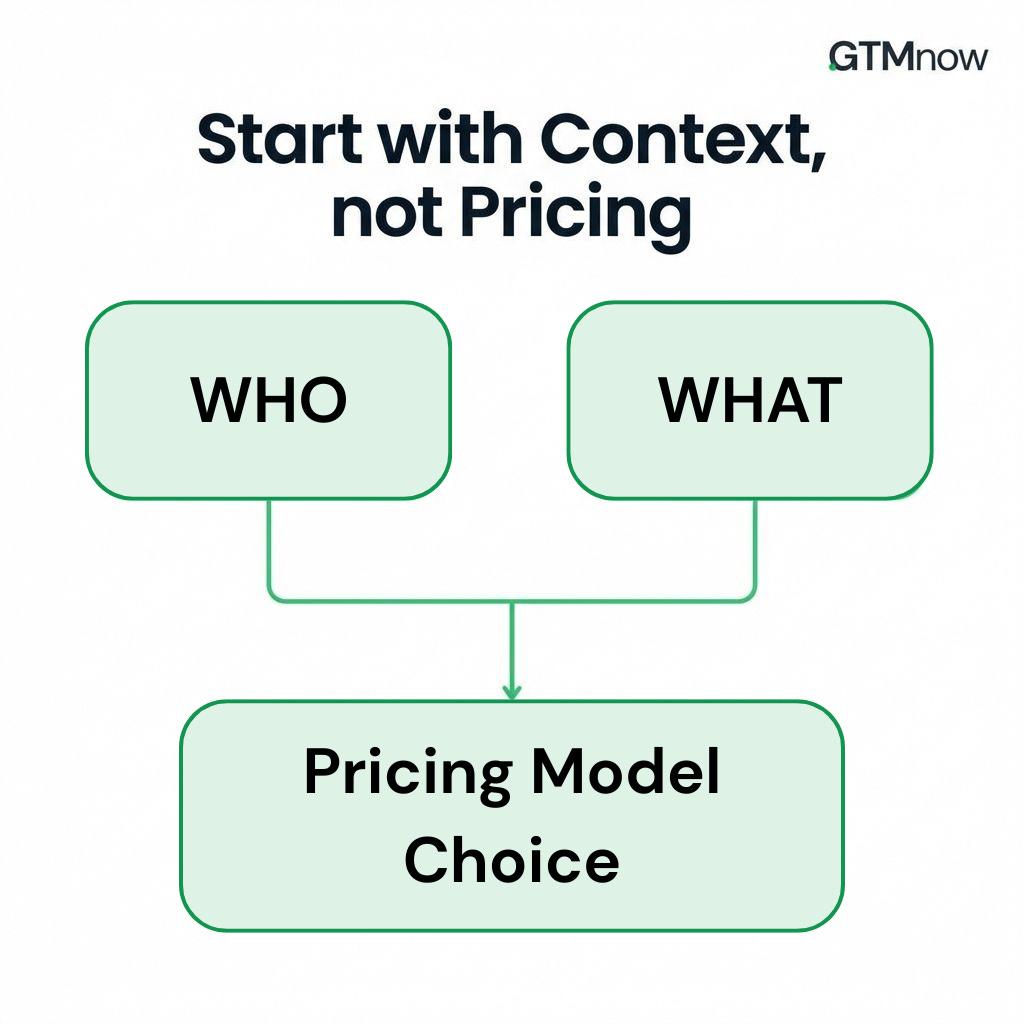

Before you look at numbers, tiers, or packaging, you need clarity on two things:

1. Who is buying

2. What they are buying

Everything else – your pricing tiers, your list price, your discounting strategy and your expansion playbook flows from these two inputs. Pricing structures vary widely depending on customer type, product category, and value-delivery model. There is no universal “right” model. There is only the model that fits your specific combination of buyer and product.

Who is the buyer?

This is about understanding the buying motion, not just the buyer’s title. Ask yourself:

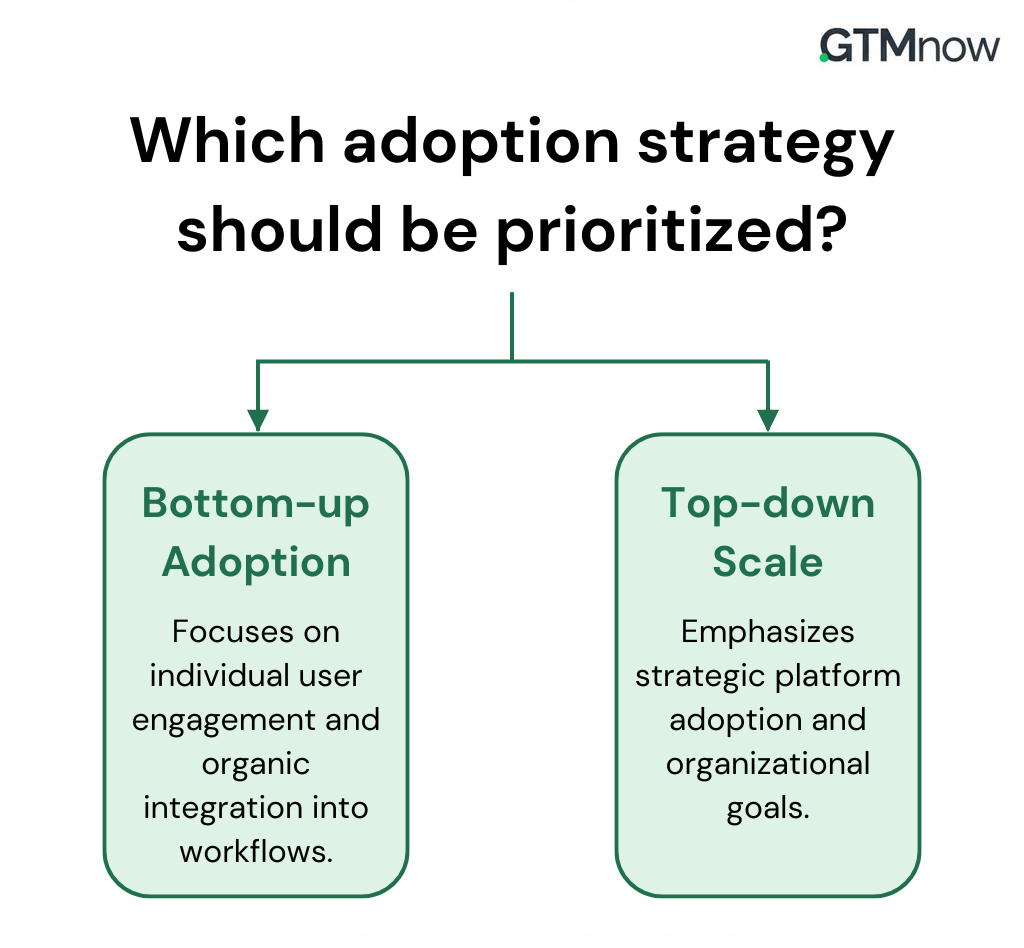

- Is the buyer an individual user discovering your tool on their own, or is it a leadership team making a strategic platform decision?

- Is purchasing happening bottom-up (an IC finds the product, loves it, and champions it internally) or top-down (an exec evaluates vendors and rolls the solution out across teams)?

- Does usage spread organically through the organization once one person adopts it, or does it require a formal rollout with training, change management, and executive sponsorship?

The answers to these questions have direct, material implications for which pricing model will work. Bottom-up adoption favors usage-based or seat-based models. These are intuitive, self-serve-friendly, and let the product’s value speak for itself at the individual level. The user doesn’t need CFO approval to start, and the expansion happens naturally as more teammates adopt. Think of how Slack or Notion spread inside organizations: one team starts using it, then two, then ten, and eventually procurement gets involved to negotiate an enterprise deal. The pricing model (per-seat) supported that organic growth motion perfectly.

Top-down sales opens the door to outcome-based, platform, or value-based pricing. When you’re selling to a VP, a CRO, or a CFO, these buyers care less about what the per-unit cost is and more about what the strategic impact will be: revenue influenced, costs eliminated, risk mitigated, time saved at scale. Your pricing needs to speak that language. A $2/conversation price point means nothing to a CFO, but “you’ll save $1.2M in annual support costs” lands immediately.

One important nuance worth flagging: if procurement or finance gets involved early in the buying process, your pricing must feel legible and defensible, not clever. A creative pricing structure that your internal champion loves but a procurement team can’t categorize or benchmark will stall in approvals. Procurement teams are trained to compare apples to apples. If your pricing model doesn’t fit neatly into their evaluation framework, it creates friction that slows everything down, regardless of how excited the end user is about your product.

What’s the product?

This is where most founders get tripped up. Your pricing model should mirror how value is created for the customer, not how the product is built on the back end. These are two very different things. A lot of founders default to pricing based on their internal architecture: API calls, compute cycles, tokens processed, and models run because those are the metrics they live with every day. But the customer doesn’t care about your infrastructure costs. They care about results.

To get this right, ask yourself three questions:

- Is value realized per user, per action, or per result? A project management tool delivers value per user (each person gets organized). An email verification API delivers value per action (each call cleans a contact). An AI sales agent delivers value per result (meetings booked, deals influenced). Each of these maps to a fundamentally different pricing model.

- Does usage correlate tightly with customer value or not at all? This is the critical fork in the road. If a customer using your product ten times more is getting ten times more value, usage-based pricing makes intuitive sense. But if heavy usage doesn’t map to proportionally more value think of a security product where value is measured in breaches prevented, not scans run, then usage-based pricing creates misalignment and resentment.

- Can customers predict their usage easily? This is the question most founders skip, and it’s the one that kills deals in practice. If your customer can’t look at their team and say, “okay, we’ll probably use about X per month, so our bill will be roughly Y,” then you’re going to hit internal resistance from finance teams that need budget predictability to approve the purchase.

When usage does not map cleanly to perceived value, pricing friction increases and expansion slows. The gap between what the customer pays and what they feel they’re getting becomes a constant source of tension that poisons the relationship over time.

If customers can’t predict their usage with reasonable confidence, they will resist usage-based pricing, regardless of how well-aligned it is in theory. The theory doesn’t matter if the buyer can’t get budget approval.

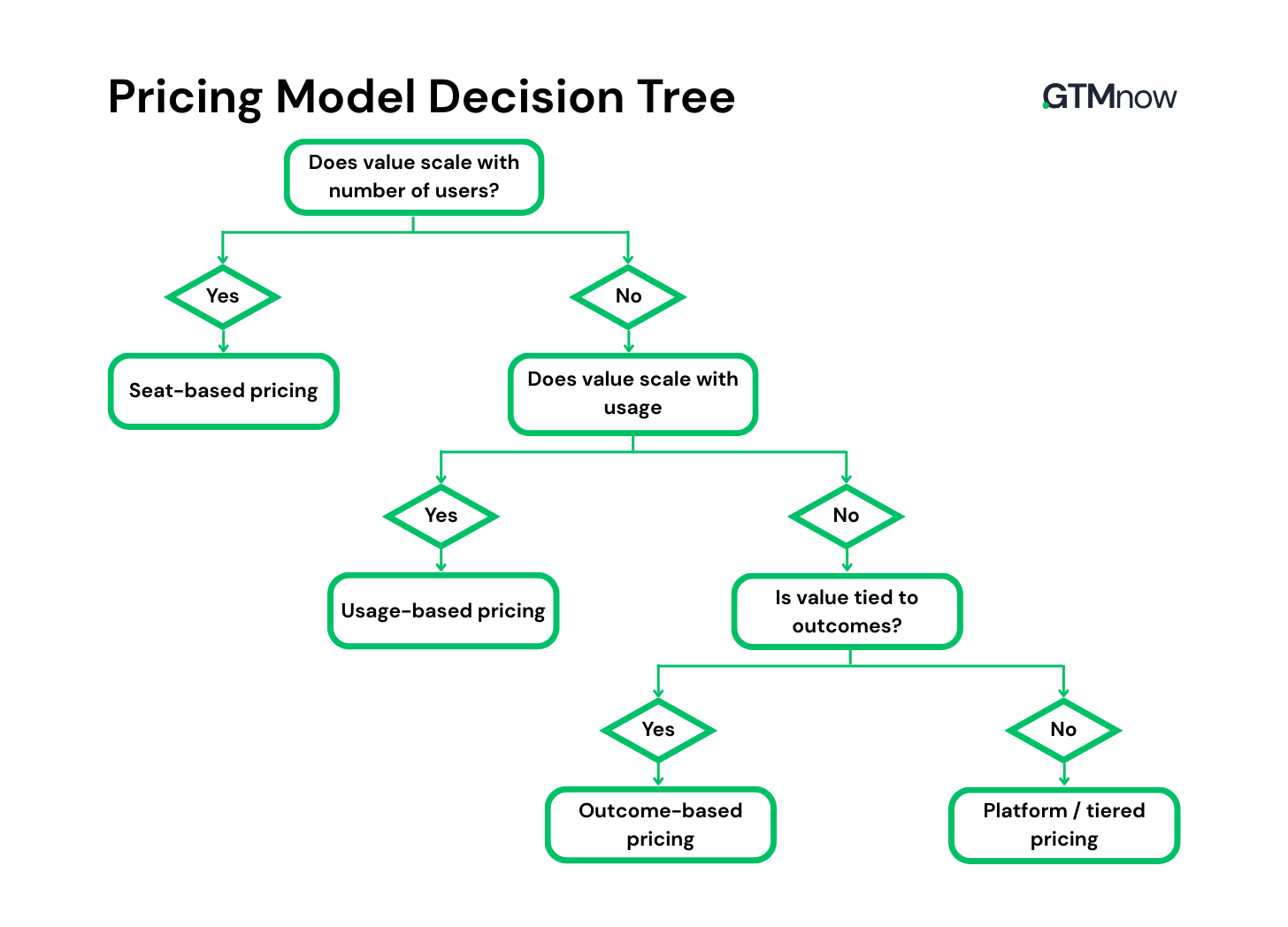

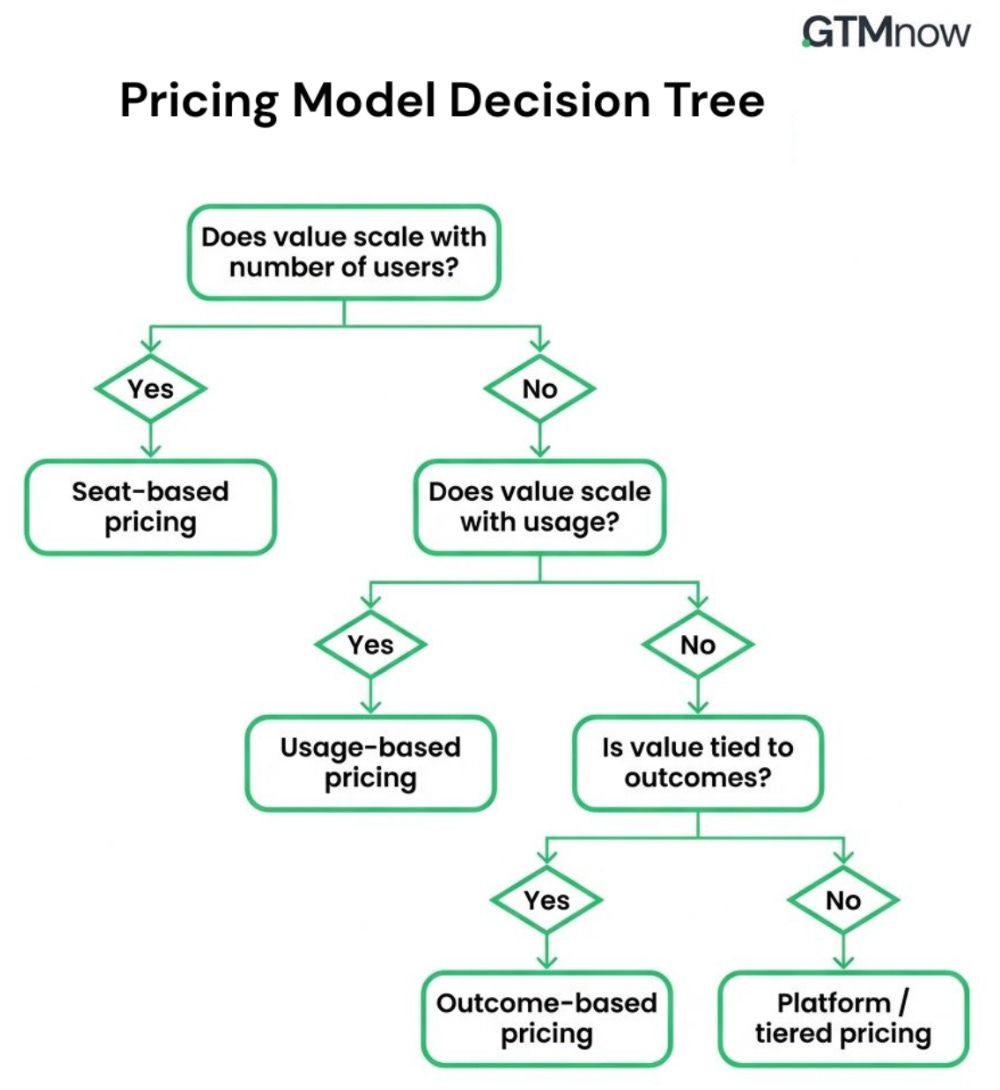

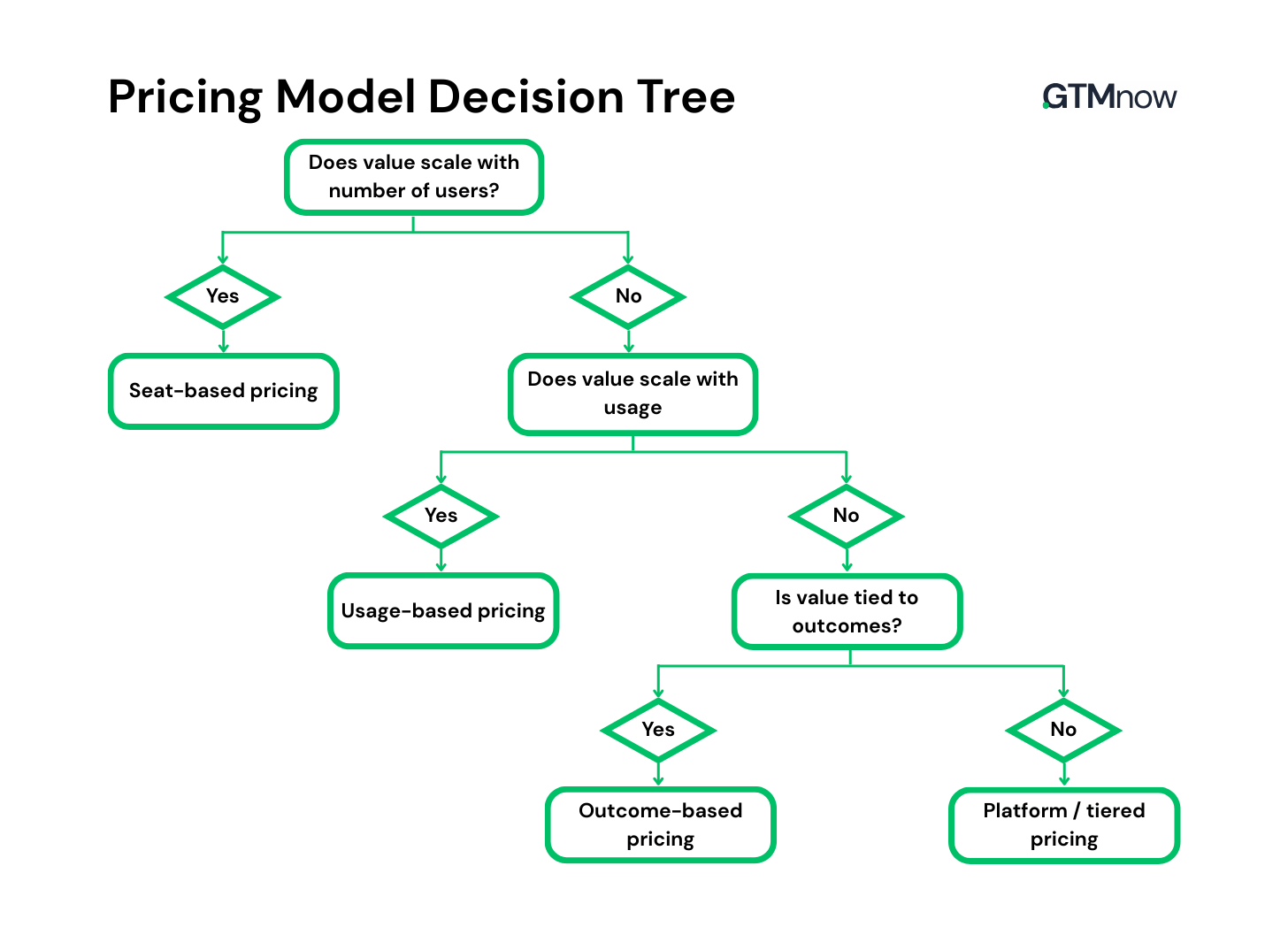

The Pricing Model Decision Tree (The “Waterfall”)

Now that you have clarity on your buyer and your product, let’s move into the decision logic. Think of this as a progressive filter, not a checklist. Each step either routes you to a pricing model or sends you to the next filter. You’re not choosing from a menu, you’re narrowing through a sequence of questions until the right model (or combination of models) becomes clear.

Step 1: Does the value scale with the number of users?

Yes → Seat-Based Pricing

This works when:

- Each user derives clear, independent value from the product, meaning if you removed one user’s access, they’d personally feel the loss.

- Collaboration scales linearly with users, more people on the platform means more value for everyone, not just more licenses sitting idle.

- The product becomes more valuable as more people join, there’s a network effect or a collaboration dynamic that makes the 50th user more valuable than the 5th.

Seat-based pricing is simple, familiar, and easy to sell, which is exactly why it dominates the SaaS landscape. Buyers understand it instantly, finance teams can model it, and sales teams can forecast it. Companies like Salesforce, Notion, and Slack have built massive businesses on per-seat models because the unit economics are clean and the expansion motion is straightforward: more users equals more revenue.

But watch out: Seat-based pricing caps expansion if only a subset of users actually get real value from the product, or if customers actively try to limit the number of licenses to control costs. Here’s a diagnostic signal that’s worth watching closely: if customers start asking, “Do all these users really need access?” you likely have a pricing mismatch. The value isn’t distributed evenly across seats, and your pricing model is forcing customers to pay for access that doesn’t translate into outcomes.

The AI era introduces an even more notable version of this problem. If one AI agent can do the work of ten human operators, per-seat pricing creates a perverse incentive: customers reduce seats as they adopt AI, shrinking the vendor’s revenue at exactly the moment the product is delivering more value, not less. This is why hybrid models are increasingly replacing pure seat-based approaches, especially in categories where AI augmentation is accelerating. If your value does scale with users, seats could still work, but keep a close eye on whether AI changes that equation for your specific product over time. This isn’t always the way that buyers want to buy.

Step 2: Does value scale with usage or volume?

Yes → Usage-Based Pricing

This works when:

- Usage scales directly with value, every additional unit of consumption translates to a proportional increase in the benefit the customer receives

- Customers naturally want to use more over time, the product creates its own pull, and usage grows as the customer becomes more embedded

- The metric is intuitive and easy to explain: API calls, messages sent, data processed, and compute credits consumed. If you have to explain the metric in a footnote, it’s probably not the right one

This model is most common in infrastructure, data platforms, and AI/compute-heavy products where the cost of delivering the product scales with usage and the value received scales in lockstep. Twilio (pay per message, per API call) and Snowflake (pay per compute credit, billed per second) are the canonical examples. In both cases, the more a customer uses, the more value they’re getting, and the more they’re willing to pay.

The appeal for founders is obvious: usage-based pricing aligns cost with value, lowers the barrier to entry (customers can start small and scale up), and creates a natural expansion loop as adoption grows within an account. Kyle Poyar’s research shows companies with usage-based components grow roughly 8 percentage points faster in annual revenue than subscription-only peers.

The critical test: Can a customer forecast their bill with reasonable confidence?

When they can’t, usage-based pricing creates budget anxiety and internal resistance that no amount of value alignment can overcome. Nearly 78% of IT leaders reported experiencing unexpected charges tied to consumption-based or AI pricing in the past 12 months. Think about what that means: nearly four out of five technology buyers got a bill they didn’t expect. That’s not a rounding error, it’s a systemic trust problem.

Unpredictability is the primary failure mode of usage-based pricing. The fix isn’t to avoid usage-based models entirely, it’s to invest heavily in transparency. Dashboards that show real-time spend, alerts before customers hit thresholds, and forecasting tools that help them model future usage, these aren’t nice-to-haves, they’re load-bearing infrastructure for the pricing model to work.

Step 3: Is the value tied to a business outcome?

Yes → Outcome- or Value- Based Pricing

This works when:

- You directly influence revenue, cost savings, or risk reduction, and you can prove it with data, not just claims

- You sell to senior decision-makers who think in business outcomes (dollars saved, revenue generated) rather than features or functionality

- Your product is deeply embedded in workflows where the causal link between product usage and business result is clear and measurable

The most striking recent example is Intercom, which launched its Fin AI agent at $0.99 per successful resolution, charged only when the AI fully resolves a customer conversation without any human intervention. The outcome was so clearly defined (a resolved ticket) and so easy to measure (did a human need to step in or not?) that the model worked beautifully. Fin grew from $1M to over $100M ARR, resolving over 1 million customer issues per week. Every time the engineering team improved Fin’s resolution rate, revenue went up, turning R&D into a direct revenue driver. You can check out the full GTMnow interview with Intercom’s President, Archana Agrawal here.

This model is powerful but dangerous early.

Why? Because outcome-based pricing requires three things that most early-stage companies don’t have yet: proof (data showing your product actually drives the outcome), trust (the customer believes your measurement methodology is fair and accurate), and leverage (enough demonstrated results that the customer accepts the pricing structure rather than pushing back on it). Without all three, customers will see outcome-based pricing as you claiming upside without sharing the downside risk, and they’ll push back hard or simply walk away.

Sales cycles also tend to run 20–30% longer because attribution debates slow procurement. For most early-stage founders, the practical move is to use outcome-based pricing as a wedge in specific high-conviction deals, prove the value with a handful of customers, build the measurement infrastructure, and gradually shift more of your revenue base toward outcomes as trust and data accumulate.

Step 4: Is the product a system of record or platform?

Yes → Platform / Tiered Pricing

This works when:

- Your product becomes infrastructure that the customer’s organization depends on, it’s not a tool someone uses occasionally, it’s the system that entire workflows are built around

- Multiple teams across the organization depend on it, creating cross-functional stickiness that goes beyond any single user or department

- Switching costs increase over time as more data, workflows, and integrations get layered on top, making the product harder to rip out with each passing quarter

This model is often paired with a base platform fee that gives access to the core product, add-ons for advanced capabilities that unlock as the customer’s needs grow, and soft usage limits that create natural upsell triggers without punitive overage charges. HubSpot is the canonical example: a free CRM as the PLG wedge, tiered Hubs (Starter, Professional, and Enterprise) that expand with the customer’s sophistication, and per-seat pricing layered on top. The model supports predictable revenue for the vendor, clean expansion paths for the sales team, and enterprise-grade packaging for larger customers who need it.

The key advantage of tiered pricing is that it gives your sales team clear upgrade conversations, “You’re on the Growth plan, here’s what Enterprise unlocks,” and gives customers a self-directed path to expanding their investment as their needs evolve. It also makes the value ladder visible: customers can see what they’re paying for today and what they’d get if they moved up, which creates aspirational pull rather than surprise costs.

Real-World Model Hybrids (What Actually Works)

Here’s the truth that the decision tree above necessarily simplifies: most successful companies don’t use one model. They use pricing layers. The decision tree helps you identify your primary model, the dominant way customers think about paying you, but the actual pricing architecture almost always involves some combination of approaches working together.

The most common hybrid patterns in practice:

- Platform fee + usage: Snowflake charges per compute credit (usage) on top of a data storage fee. The customer pays for what they consume, but the storage component creates baseline predictability.

- Seats + feature tiers: Notion and Slack charge per user but gate functionality behind tiers. The entry point is accessible, and expansion happens through both adding users and upgrading plans.

- Base subscription + outcome bonus: Intercom charges a seat-based platform fee for human agents, then layers on $0.99 per successful AI resolution for Fin. The base provides revenue predictability, the outcome component captures AI upside.

Industry pricing analyses from Metronome and SaaStock confirm that hybrid models, combining subscription, usage, and tiered components, have become the norm rather than the exception. The era of “pick one model and stick with it” is over.

The goal is alignment between value, growth, and expansion. If your hybrid model makes the customer’s buying decision clearer and your expansion motion smoother, the added complexity is worth it. If it just makes your pricing page harder to understand, simplify ruthlessly.

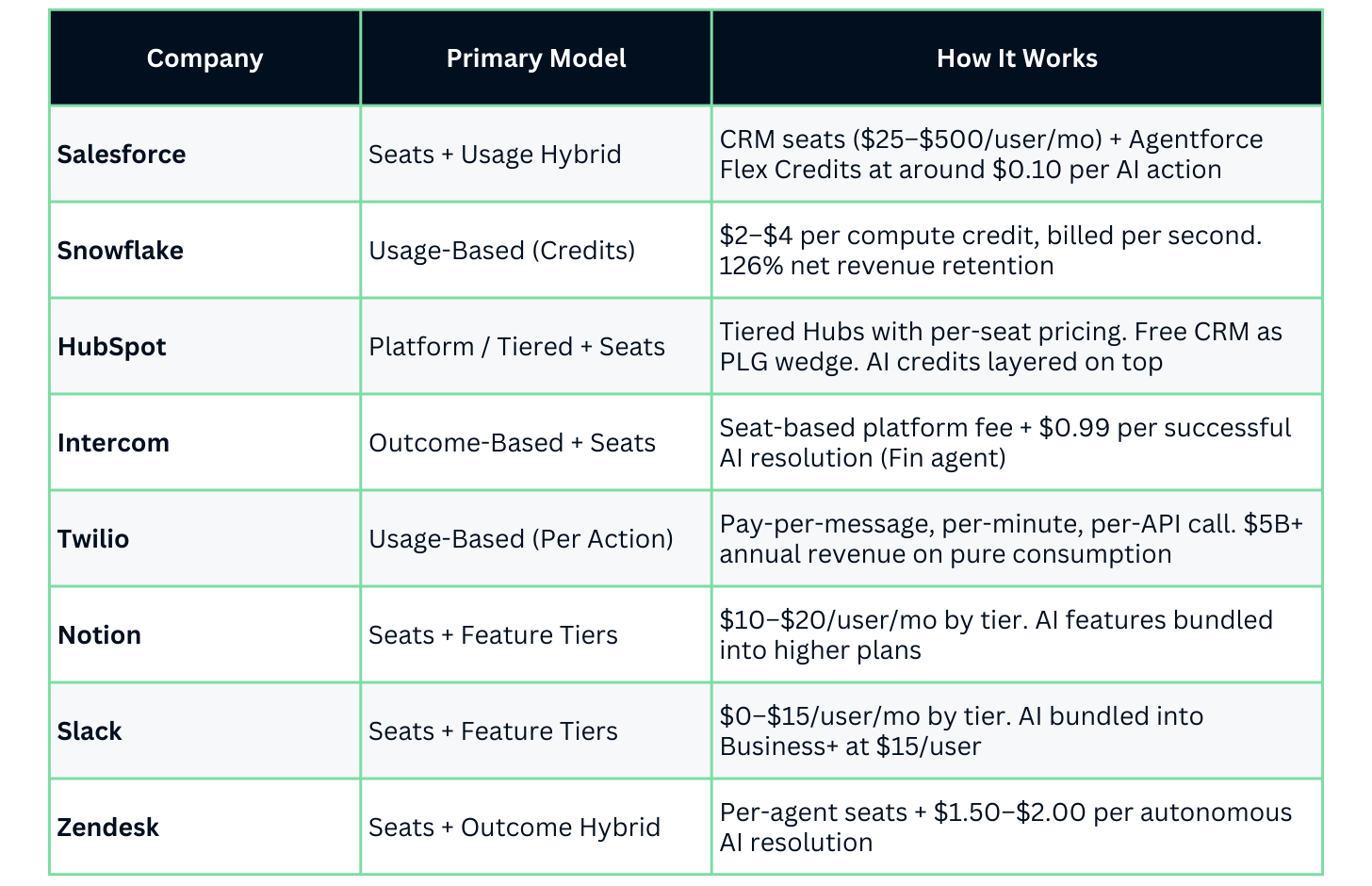

How iconic companies actually price:

What’s remarkable about this table is how much movement there’s been in just the past 18 months. Salesforce launched Agentforce at $2 per conversation in late 2024, its first major departure from per-seat licensing, then faced immediate customer backlash over unpredictable costs and pivoted to Flex Credits within months. HubSpot overhauled its entire pricing structure in March 2024, moving from bundle-based to seat-based with AI credits, and the results were strong: NRR improved from 101.8% to 105%.

The market is moving fast. The companies winning are the ones iterating on pricing as aggressively as they iterate on product. If your pricing hasn’t changed in over a year, you’re probably leaving money on the table, or worse, creating friction you don’t even know about.

Mistakes to Avoid: The Pricing Waterfall Pitfalls

The decision tree gives you a framework for choosing the right model. But frameworks only work when execution is clean. Here are the most common mistakes founders make when applying the waterfall and how to avoid them.

1. Pricing for your ICP, but selling to everyone

A pricing model built for enterprise will kill SMB conversion. A self-serve pricing page will stall enterprise sales. This is one of the most common disconnects in early-stage SaaS: the founder designs pricing for one segment, but the GTM motion is actually serving a completely different buyer profile.

The result is a pricing page that confuses everyone and converts no one. Your SMB prospects see enterprise pricing and bounce immediately. Your enterprise prospects see self-serve pricing and assume the product isn’t serious enough for their needs. If your ICP isn’t clear, your pricing will feel confused, because it is. Before you finalize any pricing model, pressure-test it against your actual pipeline: are the deals you’re closing consistent with the buyer profile your pricing was designed for? If there’s a mismatch, either your ICP definition or your pricing architecture needs to change.

2. Choosing usage-based pricing too early

Founders love usage-based pricing because it feels fair and aligned with value. And they’re not wrong, in theory. The tricky part is that buyers live in quarterly budget cycles and internal approval processes. And early-stage customers in particular want three specific things before they commit:

- Predictability: They need to know what they’re committing to before they can get budget approval

- Budget clarity: They need to explain the cost to their boss in a way that doesn’t require a spreadsheet model

- Internal buy-in: They need other stakeholders (finance, procurement, their manager) to feel comfortable with the cost structure

Usage pricing without trust feels risky to all three. The buyer can’t guarantee what the bill will be, which means they can’t get a firm budget commitment, which means the deal stalls in approvals. One way is to start with a simpler model, flat fee or seat-based, that gives customers confidence and predictability, and then layer in usage-based components once you’ve earned the right through proven value and established trust with the customer’s finance team.

3. Over-optimizing for expansion before initial adoption

If customers struggle to get started with your product, expansion won’t matter, because there won’t be anything to expand. This mistake is the pricing equivalent of optimizing your upsell playbook before you’ve figured out onboarding. Your pricing should minimize friction to start (make it easy and low-risk to say yes), delay complexity until after the customer has experienced core value (don’t overwhelm them with tiers and add-ons on day one), and earn the right to expand through demonstrated impact.

Too many founders build elaborate tiered structures with expansion triggers baked in before they’ve solved the basic problem of getting a customer live and seeing results in the first 30 days. The first pricing milestone is adoption, getting customers to use the product and experience value. Everything else is secondary until that’s working.

4. Letting pricing drift without intent

Pricing models evolve over time, that’s natural and healthy. But unmanaged drift creates chaos. What happens in practice is that sales teams start offering ad-hoc discounts, custom packaging gets created for one-off deals, and before you know it, you have fifteen different pricing variations across your customer base with no coherent logic connecting them.

Every pricing change you make, whether it’s a new tier, a revised metric, or a discount policy, should answer three questions:

- Who is this for? Which customer segment does this change serve?

- What behavior does this encourage? Will this drive adoption, expansion, or retention?

- What behavior does this discourage? Are you inadvertently punishing your best customers or creating gaming incentives?

Unintentional pricing drift is one of the most common failure modes in SaaS companies. The top performers review and adjust pricing every one to three months. The worst performers haven’t touched theirs in over 18 months. If you can’t answer the three questions above for a proposed change, don’t ship it.

5. Underpricing and anchoring low

This deserves special attention because it’s the single most common pricing mistake at the early stage, and it’s the one that’s hardest to recover from.

The logic behind underpricing is understandable: you want customers, you’re not fully confident in the value proposition yet, and you figure a low price will reduce friction and help you close deals faster. And sometimes it does, in the short term. But the long-term cost is enormous. Once customers are anchored on a low price, raising it later becomes one of the hardest moves in SaaS. The customer isn’t thinking about your cost structure or your margin needs, they’re thinking about the number they’re already paying and whether the new number feels fair relative to that baseline.

If customers are buying too quickly without any price pushback, you’re almost certainly priced too low. Some friction in the buying process is actually a healthy signal, it means the customer is taking the purchase seriously and evaluating the value.

Set your list price higher than you’d initially expect. You can always discount early deals strategically, in exchange for case studies, logo rights, or reference calls, but you can never un-anchor a low public price that the market has already internalized. Plus, you can only raise prices when you add new value.

Final Thought

There is no “best” pricing model.

There is only the model that best reflects:

- How customers experience value, not how you build it, not how you think about it internally, but how the customer on the other side of the table actually feels the benefit.

- How does your product grow inside an account? Does it expand through more users, more usage, better outcomes, or broader platform adoption?

- How does your GTM motion actually works, is your sales team equipped to sell this model? Does it match how deals actually close in your pipeline?

Get that right, and pricing becomes a growth lever. Get it wrong, and no amount of sales talent, marketing spend, or product brilliance will save you.

The founders who win will be the ones who treat pricing as a continuous product – tested, iterated, and optimized with the same rigor they apply to their core offering.

Hopefully this waterfall gives you a starting point. The market will tell you where to go from there.

Tag @GTMnow so we can see your takeaways and help amplify them.

More for your eyeballs

OpenAI reportedly finalizing $100B deal at more than $850B valuation. The deal comes as the ChatGPT-maker burns through cash as it inches toward profitability. To that end, OpenAI has said it has started testing ads in ChatGPT for free users, a gamble that could lead to more revenue or could send users running from the platform.

Salesforce signs definitive agreement to acquire Momentum. The acquisition will extend the ability of Agentforce 360 and Slackbot to ingest and analyze unstructured data from third-party voice and video channels and apply those insights directly to agentic workflows.

ZoomInfo’s team put out their 2026 GTM predictions, and the theme is clear: AI gets embedded deeper into workflow, but human signal and execution still separate teams. Worth a skim if you’re planning headcount, tooling, or pipeline strategy for next year.

More for your eardrums

GTM 179: The End of GTM Sprawl: How HockeyStack is Rebuilding Go-to-Market Around AI with Emir Atli

VC 4: How VCs Evaluate Technical Founders, with Amanda Robson (GP at mtf)

Startups to watch

Lindy – launched Lindy Assistant, an AI EA that lives in iMessage, connects to your stack, joins meetings, and actually executes. It’s less “summarize my inbox” and more “run my day.” If this sticks, the interface shift away from email and dashboards gets real.

Mutiny – is pushing the idea of the GTM Athlete, operators who can move across strategy, systems, and execution instead of staying in narrow lanes. In lean AI-era teams, that profile wins. It’s a strong call on where modern GTM talent is headed.

Hottest GTM jobs of the week

- Enterprise Customer Success Manager at Noibu (Hybrid – Ottawa, ON)

- Partner Marketing Manager at Closinglock (Austin, TX)

- Sales Account Executive at Spekit (Hybrid – Denver, CO)

- Go-To-Market Enablement Director at CaptivateIQ (Remote – Raleigh, NC/Nashville, TN/Toronto, Canada | Hybrid – Austin, TX/Menlo Park, CA)

- Senior Manager, Growth & Demand at Vanta (Remote – US)

See more top GTM jobs on the GTMfund Job Board.

GTM industry events

Upcoming events you won’t want to miss:

- Funnel ‘26: March 5, 2026 (Austin, TX)

- Spryng (for marketers): March 24–25, 2026 (Austin, TX)

- MicroConf 2026: April 12–14, 2026 (Portland, OR)

- SaaStock USA: April 15–16, 2026 (Austin, TX)

- Forrester B2B Summit: April 26–29, 2026 (Phoenix, AZ)

- SaaStr Annual: May 12–14, 2026 (San Mateo, CA)

- Dreamforce 2026: September 15–17, 2026 (San Francisco, CA)

- INBOUND: September 16–18, 2026 (Boston, MA)

- Pavilion GTM2026: September 28–October 1, 2026 (NYC, NY)

- Customer Success Week: October 5-9, 2026 (NYC, NY)

- TechCrunch DISRUPT: October 13–15, 2026 (San Francisco, CA)

GTMnow community love

Some GTMnow community (founder, operator, investor) love to close it out – we appreciate you.